My grandparent's expansive yard in northern Ohio came alive at dusk in midsummer. A pulsing veil of tiny yellow flashing lanterns filled the air. When I was a kid in the 1970s, I used to run around and catch fireflies in a quart jar so I could admire them up close. That lightning in a bottle fired my imagination and prompted me to ask, “What is this crazy magic? Why do they have a belly of fire?” I am still asking those same questions today. Those little lanterns are lodged deep within my psyche even as they disappear from the landscape.

THIS handful of grass, brown, says little.

This quarter-mile field of it, waving seeds ripening in the sun, is a lake of luminous firefly lavender.

Prairie roses, two of them, climb down the sides of a road ditch.

In the clear pool they find their faces along stiff knives of grass, and cat-tails who speak and keep thoughts in beaver brown.

These gardens empty; these fields only flower ghosts; these yards with faces gone; leaves speaking as feet and skirts in slow dances to slow winds; I turn my head and say good-by to no one who hears; I pronounce a useless good-by.

Carl Sandberg

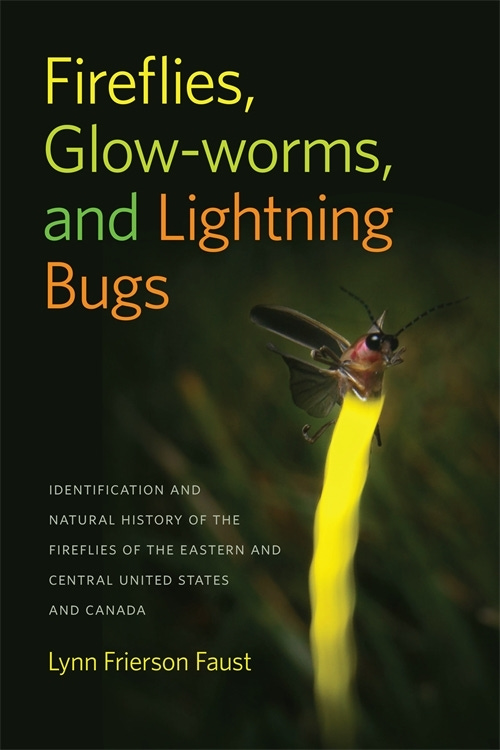

People have been fascinated by fireflies for thousands of years. Cultures around the world revere them. Dedicated fireflyers are studying this group of beetles and working to protect the 2,200 species that occur worldwide. There are 75 species that live in the eastern US. The more we study them, the more miraculous they become. We know that these little beetles contain a diverse mix of defensive chemicals called lucibufigans in addition to the complex chemical cocktail that lights up their abdomens.

Researchers have also learned that fireflies need it to be dark at night. Our love of light is causing problems. Fireflies are blinded by bright light. 100 million years of evolution have not equipped them to deal with such an unnatural thing as a bright night. So now, the fireflies struggle to see each other as we sit inside mesmerized by a different form of light. The light of our screens also blinds us and limits our ability to appreciate the tiny yellow lights flashing outside our door.

I try to maintain a balanced perspective by stepping off of the treadmill of modern consumer culture and slowly walking out into the soft green grass. Turning away from the screens and tuning into nature. I tell myself that it is okay to enter a fallow time, to take a break, pause, and relax.

I encourage my kids to take breaks too. I tell them that they do not need to compete anymore. They have full rides in college. The most important thing now is to figure out what you most want to do with your life. To figure out how to align your values and your work. The next day I hear them fall back into familiar patterns of thinking. Mere words cannot alter a lifetime of conditioning.

I try to help them connect with nature. I often ask how I can help them feel the pull of nature as strongly as they feel the pull of screens. It is a pitched battle, and nature is losing. The virtual world enthralls as the real world recedes.

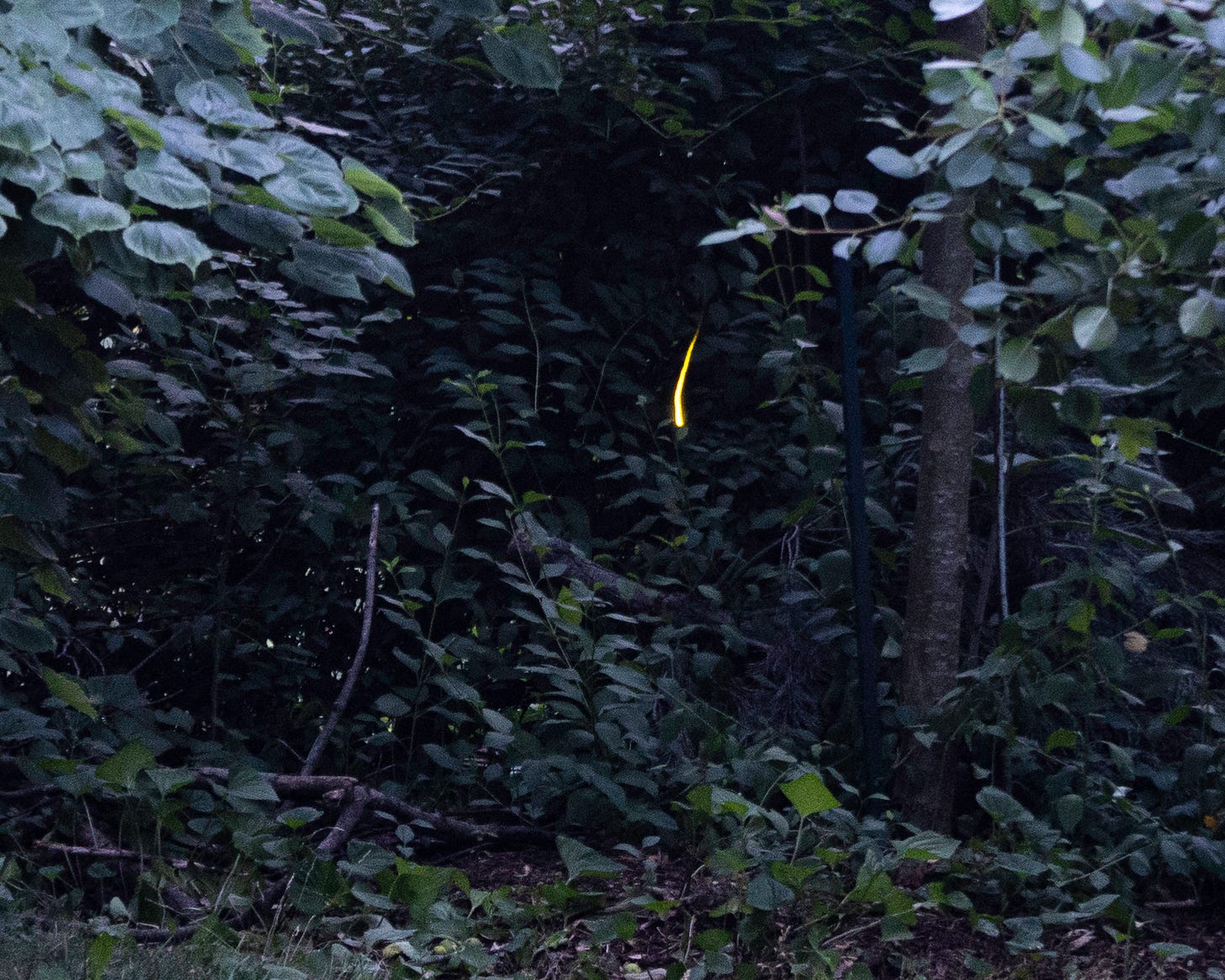

I keep trying. Sometimes, we have subtle victories. When I saw the first firefly light up in our backyard on June 21, I corralled my kids into the garden, where we stood in the fading light. At first, our time together felt awkward and begrudging. All was still and the fireflies seemed to be off in the distance. In less than a minute, things settled down and fireflies descended.

They appeared out of nowhere. Tiny amorous beacons hovering around us. Flashes of light are their love songs. They are longing for connection. For the first time in my life, I stopped and really noticed them and what they were doing. I slowed down enough to see that these little beetles had an agenda. The males were hovering in the faint dusky shadows near vegetation and flashing for females. They were eagerly awaiting the demur response flash from the female that signals she is ready to mate. Time is of the essence, as adult fireflies only live for a couple of weeks.

The males were focused on the task at hand. They would fly within a few feet of us and hover nearby. Little yellow flashes and streaks filled the air. We were still and silent for a few minutes. My kids were entranced. They stood still, glanced from side to side trying to track the little flashes, as they absorbed the show. I saw subtle smiles. Maybe this experience will serve as a small antidote to nervous systems shaped by video games. It could resurface later in life and help them find balance. We walked under the elderberries on our way back to the house. We were calm and at ease. I felt a compelling sense of connection to my kids and the fireflies.

The fireflies carried away some of our burdens and transmuted them into light. Each firefly absorbed our concerns and burned them up. Every flash our salvation. Our fate is tied to the fate of the firefly. We carry the same light inside. Their little light is our little light. Together, we illuminate the path.

This little light o’ mine, I'm goin’ let it shine

Let it shine, let it shine, let it shine.

Everywhere I go, I'm goin’ let it shine

Let it shine, let it shine, let it shine, let it shine, let it shine.

In my neighbor's home, I'm goin’ let it shine

Let it shine, let it shine, let it shine.

Thank you for sharing this experience. I grew up with fireflies in Missouri, but have spent most of my life in Oregon, where I live now. No fireflies for us, sadly.

In upstate N.Y., when I was little, we used to run and catch fireflies in a bottle. It was quite a challenge following a firefly's regular flashes and trying to anticipate where he'd be the next time he'd light up. Once we had enough in the bottle, their individual intermittent beacons combined to make a little lantern.