Learning to be a Good Neighbor in Subirdia

People and birds seek refuge and common ground in the suburbs.

Rural areas in the Midwest are denatured and depopulated. As people leave, the capacity for stewardship is diminished. Exotic plants and industry have their way with the land. It is tempting to think that somehow high-quality natural habitat exists in the countryside under these conditions, but it is complicated.

The declines in insect and bird populations we are experiencing are driven, in part, by our toxic food system. Open space and natural habitat do not necessarily provide what people and wildlife need to thrive. The chemical cocktail that runs off of farm fields dissolves in the water, and the systemic insecticide coatings on the seeds that are planted disorient and kill birds that eat them. This toxicity, coupled with habitat loss and degradation, disrupts and weakens the web of relationships that support life.

Our food system is a direct manifestation of our disconnection from nature. The way forward is through connection, and the place to connect is where people and nature currently coexist; on the margins and in the suburbs.

For many years and for many reasons, people and wildlife have moved to urban areas. The suburbs, in particular, are a leafy refuge. We are taking refuge in the most hospitable places available to us. We currently add 1,000,000 acres of urban area in the US each year. It is an urban tsunami.

Fortunately, people and birds are resilient, and we can ride this wave rather than fight against it.

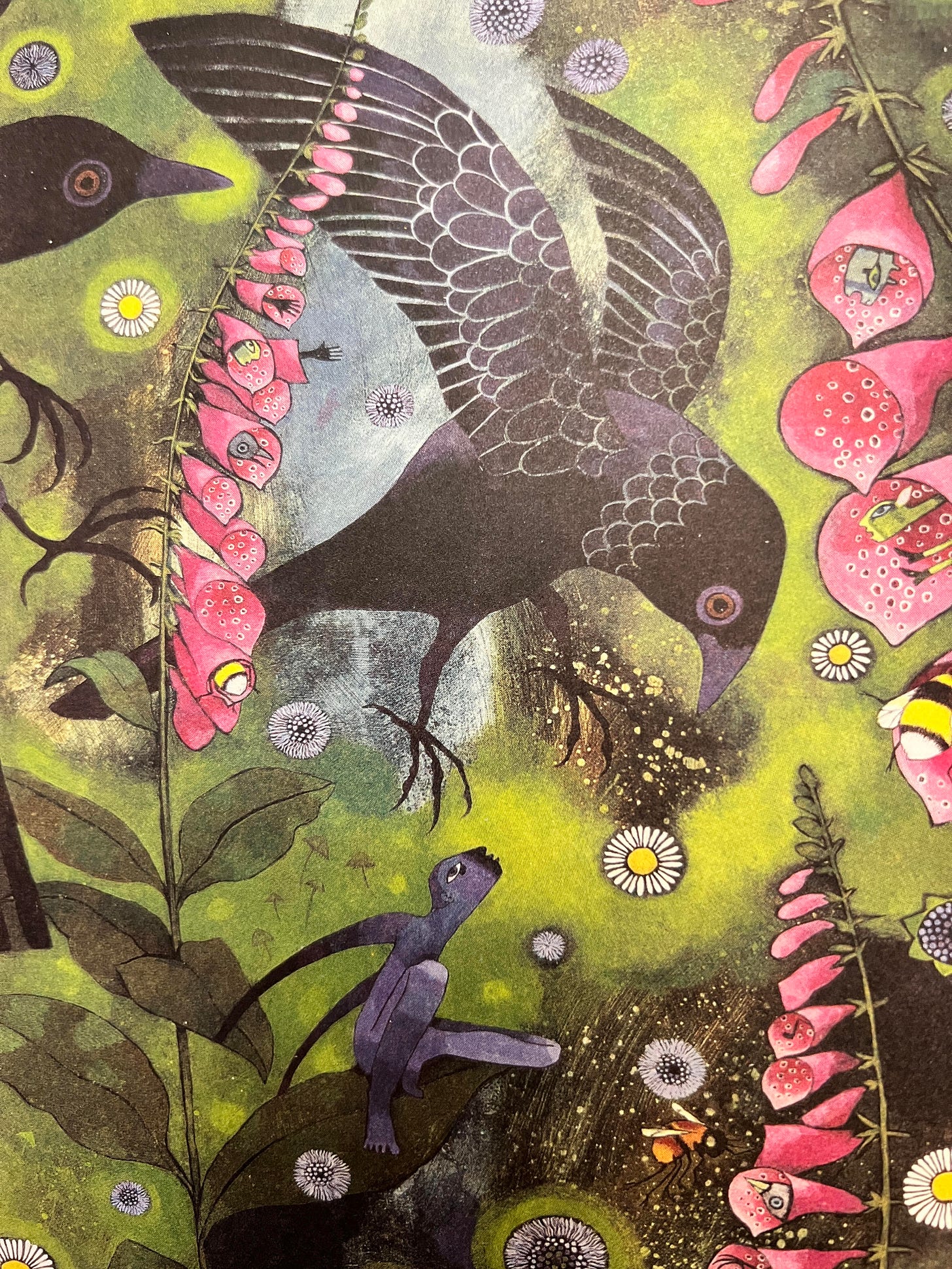

Within our urban oases, we can engage with nature on our own terms. We have agency in this space and can embrace our inherent sensitivity and tune in to the natural world where we can become more calm, connected, at ease, centered, and humble. Signs that we recognize that we all have an infinite itinerary, as part of nature, our beautiful lives woven into the tapestry of all life. A tapestry composed of hearts, minds, wind, wingbeats, and threads of green.

A new way of relating to nature can help us manage the challenges of urban development. Concrete is foremost among them. In addition, most lawns are simplified monocultures of exotic grass treated with toxic chemicals. Our aversion to messiness creates a sterile landscape. Despite these challenges, birds are hanging on in the margins. They are adapting to the suburban matrix, which provides some of the best habitat in the country.

On any day of bird watching, you can see more birds in Central Park than in Yellowstone National Park (eBird). This same trend holds across all temperate zones. There’s often more bird diversity in suburbs than in wilderness areas.

John Marzluff and a team of graduate students have studied bird diversity in urban and rural areas of the US for decades, and he describes his experience in Welcome to Subirdia. What they have found is that 10 to 15 species of birds inhabit urban cores. As you move out of city centers to the suburban fringe, bird diversity doubles, where it is common to see 30 species of birds. As you move into the countryside and large natural areas, bird diversity drops.

Large contiguous natural areas are important for a variety of reasons, including their ability to support the most sensitive species. Still, when you consider bird diversity, the suburbs stand out due to the varied habitat conditions and the diversity of plant species, which leads to a diversity of insects and other resources that birds need.

We are also getting better at learning to coexist with wildlife. London serves as a model in this regard. In 1900 there were 25 different species of birds recorded in London. In 1975 there were 40 species, and in 2012 there were 60.

This dramatic increase in bird diversity is attributed to improved attitudes towards wildlife, better habitat in city parks and yards, and decreased pollution. This nearly three-fold increase in the species of birds serves as a model for us and shows the dramatic improvements we could realize through landscaping our yards for wildlife.

Rob Blair, at the University of Minnesota, has categorized birds based on their responses to urban areas. Birds fall into three categories: avoiders, exploiters, and adapters. The avoiders are sensitive species that need large protected natural areas to thrive. Exploiters have learned to take advantage of us and our urban habitat and are generally doing fine. Adapters have learned to coexist with us in suburban areas.

The more diverse habitat we can learn to support, the more avoiders and adapters can live among us. Birds disappear as the resources they need fall victim to our propensity for tidying up our surroundings. Mary Oliver describes this in a poem about her backyard:

“I had no time to haul out all the dead stuff, so it hung, limp or dry, wherever the wind, swung it over, or down or across. All summer stayed that way, untrimmed and thickened. The paths grew damp and uncomfortable, and Mossy until nobody could get through but a mouse or a shadow. Blackberries, ferns, leaves, litter, totally without direction management supervision. The birds loved it.”

Restoring habitat in your yard is a form of community building. Birds are an indicator of the larger community. More birds mean more life and beauty.

In order to build this community, we need to appreciate the value of many small patches of habitat in yards knit together into a network. We must push back against the notion that bigger is better. Kyo Maclear acknowledges this trend in her beautiful book Birds Art Life.

“Small trips were city parks with abraded grass, the occasional foray to the lake woods of Ontario, a dirt pile. Smallness did not dismay me. Big nature travel—with its extreme odysseys and summit-fixated explorers—just seemed so, well, grandiose.

The drive to go bigger and further is just one more instance of the overreaching at the heart of western culture.

I like smallness. I like the perverse audacity of someone aiming tiny.

Together we would make a symbolic pilgrimage to the wellspring of the minuscule.”

The small natural spaces we create in our yards can be full of wonder. We can have wellness and water spring forth from our yard as we strive to be like a kid again. The flowing water, fluttering leaves, dappled light, and bird song are all we need.

These oases of abundance in our own yards can work together to support larger reserves of grasslands and forests within and adjacent to suburban development. Young birds produced in these grasslands and forests disperse into suburban neighborhoods, where they visit gardens, water features, and birdfeeders. This helps increase the survival of adults and their young. Functional connections between suburban development and larger, protected natural areas are critical to support full bird diversity.

We are stewarding a new amalgamation of habitat and wildlife in urban areas.

Birds are adapting to us and our urban habitat. They are doing what all life does, evolving by natural selection. Their genes and cultural traditions are changing. This genetic and cultural evolution occurs in all sentient and social species, and it can happen fast.

Juncos breeding in urban areas have developed darker tails and bolder and less easily stressed personalities. This enables them to coexist with people. The darker tails are partly a response to females selecting males that stick around and help feed young. Males with more white tail feathers tend to fly off to fight with other males. Males that care for their families and spend less time fighting are increasing in the population.

This rapid evolution in response to novel environments is the new normal. It’s called contemporary evolution. It began in earnest during the industrial revolution. We shape evolution as evolution shapes us.

Sometimes evolution is a whisper. The world is drawing us into new relationships. The voices of birds are emerging from the din. Imagine relaxing next to a small pond in your backyard. A chickadee lands on your shoulder, and this is what you hear. “Don’t hunker down, jump up, leap out, open to possibilities, stand in the sunlight, feel the wind, hear the songs, touch the plants embrace it all.” The New Farmers Almanac

Nine Commandments of wildlife.

From Welcome to Subirdia

Do not covet your neighbor's lawn.

Keep your cat indoors.

Make your window more visible to birds that fly near them.

Do not light the night sky.

Provide food and nest boxes.

Do not kill native predators.

Foster a diversity of habitats and natural variability within landscapes.

Create safe passages across roads and highways.

Ensure that there are functional connections between land and water.

Snow Geese

We stopped on a sandy ridge under the canopy of a Mockernut Hickory to scan the wetland below us. Canada Geese and Mallards were foraging near the shore, and Trumpeter Swans were visible in the distance. We slowly made our way down the trail to the edge of the wetland. As the canopy opened, the calls of the swans filled the air. I could feel myself relax.

At this point, we noticed a faint new section of the avian symphony enter our consciousness. It barely registered at first as it drifted through the azure sky. We scanned the distant horizon with our binoculars and eventually saw tiny white spots above the Illinois River. Snow Geese were on the move.

Snow Geese are one of the most abundant species of waterfowl in the world. They have increased dramatically in recent decades, and their numbers are estimated to be around six million. Although it is encouraging to see wildlife succeeding, the overabundance of snow geese creates problems in the Arctic, where they overgraze the vegetation.

We watched the large flocks fly off toward Emiquon National Wildlife Refuge, and we hopped in our car to follow them. As Emiquon came into view, we saw large white amorphous patches on the sprawling wetland. We hiked down to the water's edge and entered a world dominated by geese.

They filled the water and the sky. Their constant calls reverberated across the waves. They are smart and wary birds that keep their distance from people. Watching them through binoculars, you can see their dark shining eyes looking back at you. Each ever-vigilant goose is part of a flock of thousands. Collective intelligence supports an ancient survival strategy.

The murmuring of the flock occasionally increases in tempo and volume, and there are many instances of groups of birds taking flight and settling back down nearby. Every once in a while, the entire flock takes flight. This is a breathtaking moment. The first time it happened, I literally gasped!

Powerful wings and resonant calls create a loud rushing sound accompanied by what appears to be utter chaos. Thousands of birds fill the air. The white, gray, and black murmuration shapeshifts, rises, and falls, fluid as water and completely mesmerizing. Elegant synchronicity emerges from chaotic beginnings as each bird gracefully rises into the sky. Flowing ribbons of geese twist and turn, merge and emerge from the great flock, and float off into the distance.

Cars stop on the side of the road, and casual passers-by are now birdwatchers. This is one of our great spectacles of bird migration and a conspicuous sign of natural abundance. Snow Geese are on the rise, and they have become exploiters of sorts. They are taking advantage of a warming tundra and agricultural crops. We have shaped the landscape to their liking, and they are now a beautiful conundrum.

It was breathtaking to see the geese in person! If you’d like to see this sort of spectacle, find people from your local Audubon chapter for advice.