From north to south, we drove into spring and a unique Gullah Geechee food culture in South Carolina. The first stop on our trip was a grocery store, where we stocked up on Carolina Gold rice and collard greens. The huge, two-pound bunch of collard greens was a surprise and an indication of regional cuisine in the southeast. We would have to buy four bunches of collards in the Midwest to reach an equivalent amount. The clerk at the cash register was surprised by two things - that we had driven to South Carolina to watch birds and that we intended to eat the greens. Our next stop was a fish stand where we purchased beautiful local seafood. When we reached our final destination on St. Helena Island, we encountered a fascinating mix of people, birds, and food.

The people and birds were drawn to the great expanse of blue water on the coast; the historic low-country cuisine was part of a different blue zone. Blue Zones are areas in the world where people live longer, healthier lives. These areas have been extensively studied, and they share a few things in common, including a largely plant-based diet based on rice, beans, nuts, and greens. The new Blue Zones American Kitchen cookbook features recipes from communities across the US that follow these principles.

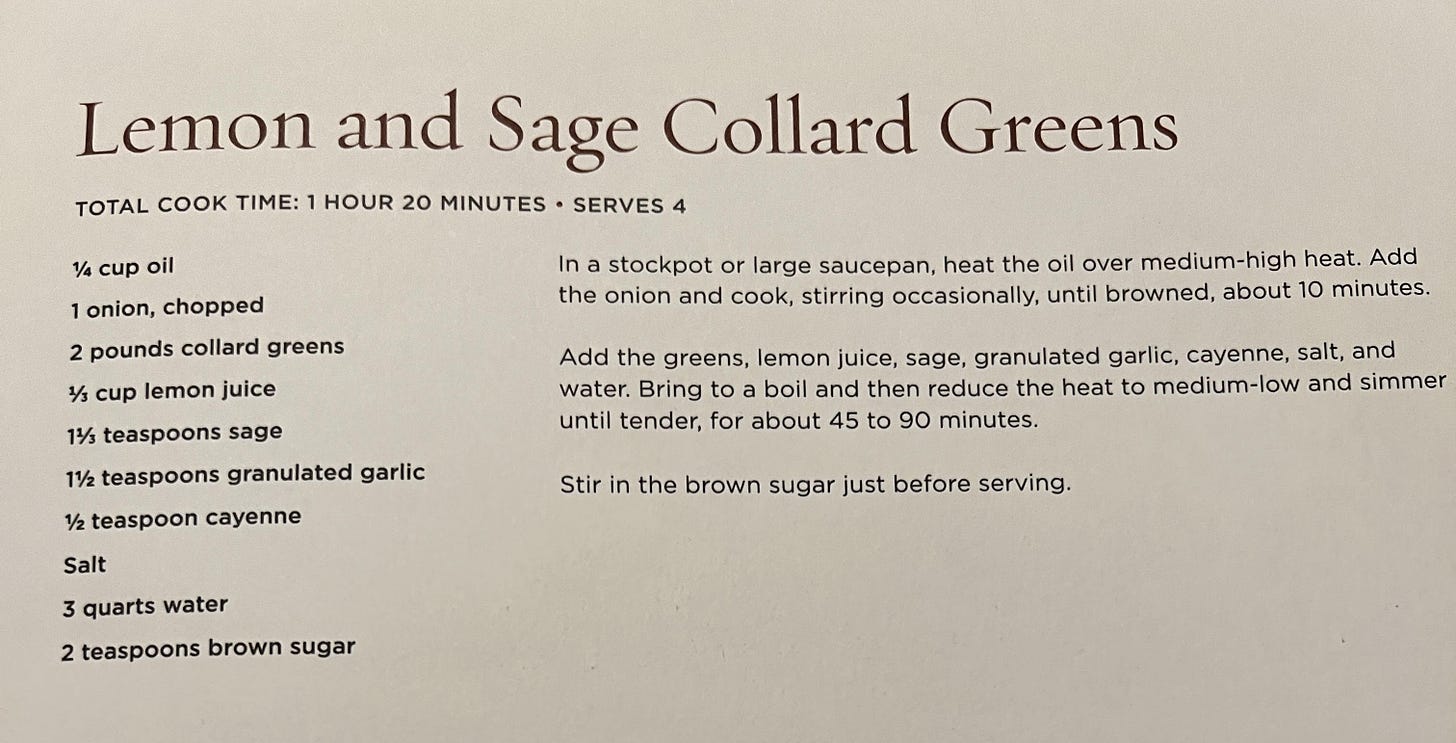

One of our favorite recipes in this book is the collard green recipe from Gullah Grub restaurant in South Carolina. The greens are melt-in-your-mouth tender and delicious. Learning how to cook collard greens and then experimenting with other greens is an important skill and a way to add more greens to your diet. After reveling in Carolina Gold rice and collard greens, we walked down to the beach to experience a different blue zone.

On our first visit to the beach, we met Peggy, a shorebird steward with the local Audubon chapter. She gave us a tour and told us about her work educating tourists about shorebirds, horseshoe crabs, and sea turtles. She also recommended several bird hotspots to visit, including a heron and egret rookery in a nearby neighborhood. Rookeries turned out to be one of the surprise highlights of our trip. I am used to rookeries in the Midwest, where the nests are in the tops of tall trees. When we approached the rookery off Kelp Court, a small residential cul de sac, we saw egrets and herons crowded into low-growing shrubs. To my surprise, these eye-level birds were sitting on nests. They were also habituated to people, hence the intimate photos of birds in breeding plumage. One of the reasons they are comfortable being near the ground is that they have an attendant alligator that minimizes the threat from predators below.

Peggy and several other locals also encouraged us to visit Cypress Wetlands in Port Royal, SC. This urban wetland helps manage stormwater runoff and provides remarkable wildlife viewing opportunities. The city of Port Royal and dedicated volunteers worked together to restore and manage this wetland to promote native plants and the rookery. A complex and delicate balance exists between water levels, plants, alligators, and birds. When everything comes together, the results are magical.

When we got within a few blocks of the wetland, we started to see and hear the birds. As we walked the trail into the preserve, we entered what appeared to be a zoo exhibit for a southern swamp. Alligators were resting on the bank twenty feet away under the low-spreading limbs of live oaks festooned with long-hanging strands of lichens. Herons, egrets, storks, ibises, gallinules, and other birds were everywhere, and they were almost completely oblivious to people. I could not walk ten feet without being compelled to take a picture. It was awe-inspiring.

The main boardwalk runs over the open wetland and, when we visited, was full of people appreciating nature. Most people carried a phone, and they were taking pictures and videos of the scene around them. When I got out on the boardwalk, my camera and binoculars attracted the attention of people who started asking me questions about the birds. Before I knew it, people were lined up to show me images on their phones so I could identify birds for them.

One of the critical benefits of the boardwalk was the separation from the alligators. For most of the trip, we observed the alligators sunning themselves out in the open, and they rarely moved. On our last visit to Cypress Wetlands, temperatures reached 80 degrees, and things changed. We were on the boardwalk when we heard a tremendous splash and saw an 8-foot-long alligator thrashing in shallow water.

For the next 15 minutes, this alligator charged around the wetland trying to capture an unwary victim. Small alligators, birds, and turtles fled from his approach. It was shocking to see such a powerful and blatant display of hunger and aggression. This alligator was the top predator, and he was hungry. He would come to rest after coasting into vegetation, but his large tail kept undulating in the water. He was fired up. Most of the birds seemed to be used to this behavior, and they would simply hop up to perch a few feet above the water when he passed by.

While this alligator spectacle was happening just below them, the herons and egrets were busy building nests, incubating eggs, and tending to newly hatched young. The rookery was spectacular. The breeding plumage of these birds is used to attract a mate, but their shapely plumes appear to be expressly designed for human aesthetics. The birds meticulously tended to their long, colorful plumes and frequently engaged in captivating displays.

I watched one Great Egret preen for fifteen minutes. I have never seen a bird so aware of its own beauty. It even made little cooing noises as it was preening and displaying. It practiced its displays by thrusting its head straight up in the air and then quickly dropping down with plumes expanded even when its mate was nowhere to be seen.

After watching this egret, I realized that part of the appeal of this preserve is that the wildlife and people are relaxed. They both feel safe here. This sanctuary was intentionally designed for animals, people, and stormwater retention. Work began nearly 20 years ago when the city created islands, deepened sections of the swamp, managed exotic vegetation, and allowed the animals to colonize the area. The rookery has fluctuated over the years depending on the balance between birds, vegetation, alligators, and raccoons. There have been periods when exotic trees filled in the islands and raccoons were able to hide from the alligators. They promptly ate the birds, and the rookery declined. When the exotic trees were removed, the raccoons disappeared and the rookery expanded.

We are all seeking refuge. For the birds, refuge means safety from predators. To find refuge, birds and people will go to the ends of the earth. The Red Knots on the beach here in South Carolina are on their way to the Arctic, where they will spend the summer in relative peace and isolation surrounded by an inhospitable landscape swarming with insects. From there, they will make their way halfway around the world to spend their winter in South America. Some of them end up in Tierra Del Fuego, another inhospitable area that limits human presence. This is an extreme version of what we all pursue.

People on the boardwalk and Red Knots resting on the beach amidst the crashing waves are examples of life searching for a sanctuary. We need more sanctuaries in the world for people and wildlife and, ideally, these safe spaces would allow all of us to co-exist. This is my dream and something I hope to manifest in our area.

I recently visited a local wetland back in Central Illinois, and I was surprised to see a Snowy Egret. They are not normally seen in our area this time of year. Maybe he followed me back from South Carolina? I took it as a sign. He was resting out in the middle of a managed wetland, standing there in his full breeding plumage, looking magnificent. Would he attract a mate and build a nest if he could find a safe space? Yes.

Ten minutes later, a flock of American Golden Plovers wheeled overhead, circling the wetland in a shape-shifting, high-speed flock that emitted soft calls as they sliced through the air. Their beautiful, high-contrast black, white, and gold plumage shone in the sun. They banked hard above our heads, and we could hear the wind rippling through their feathers. They were looking for refuge on their long journey, and they keep circling over land that has provided food and shelter for them for thousands of years only to find it now almost completely devoid of life. This is the crux of the issue for bird conservation. We have taken too much, and we need to find ways to give back and restore balance.

Mega-like, including the photography -- wow. Those gator shots are the epitome of creativity.

I enjoyed this writing so much. We’re in SC now & the week has been great. A visit to an Audobon Preserve was a delight & I recorded 19 birds in 10 minutes. We’ll check out the Port Royal wetlands.