I have the best seat in the house, in the back, under the goose nest. The show is set to begin in 15 minutes, but, only if I sit still and stay in the shadows. I can hear hundreds of ducks calling as they circle over the blind. The female Canada Goose sitting on a nest on the roof is rearranging sticks.

I managed to get into the blind with minimal disturbance despite the fact that there are hundreds of ducks in the wetland in front of the blind. I belly-crawled over the top of the levee for the last 20 feet to hide from the wary birds. My slow crawl was only partially successful, and the birds knew something was happening. They could hear the door scrape against the floor and the shish of my coat fabric brushing against itself as I got set up. They very subtly drifted away from the blind, but it would not be long before they attempted to return to the sheltered shallow water in front of the blind.

There is a gaudy cast of characters in the wetland. They are wearing outrageous costumes and are prone to outbursts. Love is in the air. Suitors strut and display for females while their competitors wait their turn nearby.

Some birds have formed pair bonds, and the males trail the females as if on a string. They are rarely more than ten feet apart. The males are brilliant, and they frequently call attention to themselves by throwing their heads back and engaging in synchronized swimming with the females.

I am sitting four feet back from the opening of the blind, completely hidden from view, and I can hear the ducks getting closer. They are just out of view now, circling, foraging, calling, and gradually moving into my field of view. A tiny Green-winged Teal is the first duck to appear. He flies in and lands on the water with a splash. I close my eyes and look down and off to the side. This is my first test. He scans his surroundings and eventually determines that the area is safe, and he starts foraging. Now the others will come. The teal’s content body language will draw them in.

Over the next 10 minutes, 8 different species will appear within view through my square window on the world. Ring-necked Ducks are the next to pop up. They dive and forage for aquatic plants and invertebrates and rise up to the surface after 10-15 seconds underwater. You can see the water roiling just above their paddling feet, and they tend to pop up close to the center of that circle of disturbance. When they rise up to the surface with an upwelling of water, they first appear under a mound of water that quickly thins and rolls away. For a brief moment, they are covered in a thin silver sheen.

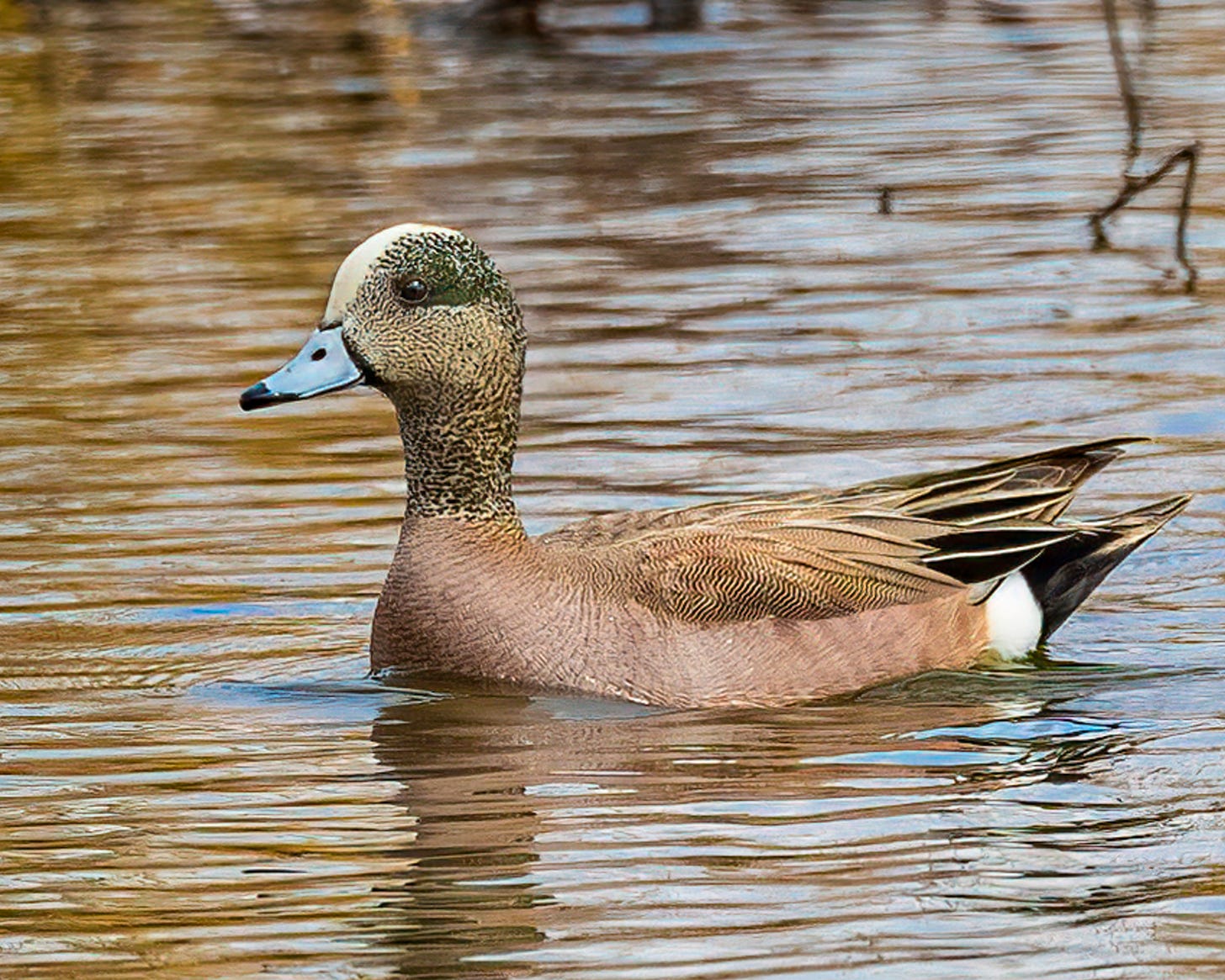

Once this group of Ring-necked Ducks moved in, the rest of the mixed flock gradually joined them. Coots were next to appear, rapidly snapping up tiny aquatic plants from the surface of the water. Gadwall and American Widgeon made brief appearances. The widgeon was particularly striking with his intricately patterned plumage - an orange, red, and mauve base color topped off with a complex black and white mottled pattern on his neck that thins out on his cheek only to coalesce into a dense pattern just above his eye. A bright white stripe runs down his forehead and meets a light blue bill.

I am surrounded by 30-40 waterfowl that are contentedly feeding, preening, and resting. Their calls have quieted down; they are moving more slowly, and spending more time sitting still. I can feel their contentment seep into me. I feel more content. We are at peace.

I carry this contentment with me as I hike out and start the drive back home. I am thinking about the wetland oasis thrumming with life when I turn onto a county road and enter the vast Grand Prairie region of central Illinois. I am imagining the ducks and water following me and spreading out across the bare corn fields like a boisterous vibrant green wave of life, revivifying a barren landscape.

In some places, you do not even have to imagine life returning to the land. It is there for all to see, winding across the landscape in a wide silver ribbon. I pull off on a side road and stop in a low spot with a view of Six Mile Creek shining in the sun. Clouds of ducks fill the air above the creek, and they swoop in and land on the open water.

The land is farmed right through the creek. It is as if they think the creek does not exist. Tile drainage and the nearly complete absence of perennial cover have greatly diminished the creek, but at this time of year, it appears on the landscape like a mirage. I think creeks should not be farmed. The land is showing us where to create buffers of native vegetation that would add resilience to a fragile landscape that exports vast amounts of soil to the Gulf of Mexico every year.

The water is rising up in a de-natured landscape, stimulating nature to rise up in the consciousness of people in this place. Wild birds in a wild sky overshadow the rolling prairie landscape, infusing it with ancient rhythms that resonate deep in our psyche. You have to work hard to suppress much of our human nature to not see this spectacle. This comes at a great cost to people and the land.

Fortunately, the future holds great promise. New young farmers are coming back to the land, and they bring a different worldview and priorities. They know that we are part of nature, and the way to succeed in farming is to work with nature to create resilience through diversity and respect for the more-than-human world.